Afghanistan

| Islamic Republic of Afghanistan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Afghan National Anthem |

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Kabul |

|||||

| Official language(s) | Dari (Persian) and Pashto[1] | |||||

| Demonym | Afghan [alternatives] | |||||

| Government | Islamic Republic | |||||

| - | President | Hamid Karzai | ||||

| - | Vice President | Mohammad Fahim | ||||

| - | Vice President | Karim Khalili | ||||

| - | Chief Justice | Abdul Salam Azimi | ||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | First Afghan state[1] | October 1747 | ||||

| - | Independence | August 19, 1919 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 647,500 km2 (41st) 251,772 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | negligible | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2009 estimate | 28,150,000[2] (37th) | ||||

| - | 1979 census | 13,051,358 | ||||

| - | Density | 43.5/km2 (150th) 111.8/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2009 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $27.014 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $935[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2009 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $14.044 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $486[3] | ||||

| HDI (2007) | 0.352 (low) (181st) | |||||

| Currency | Afghani (AFN) |

|||||

| Time zone | D† (UTC+4:30) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .af | |||||

| Calling code | 93 | |||||

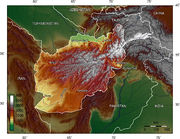

The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, commonly known as Afghanistan, is a landlocked country in south-central Asia.[4] It is bordered by Pakistan in the south and east, Iran in the west, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in the north, and China in the far northeast. In addition; India claims a border with Afghanistan at the eastern Wakhan corridor as part of its claim on the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Kashmir currently controlled by Pakistan.[5][6] The territories now comprising Afghanistan have been an ancient focal point of the Silk Road and human migration.[7]

The land is at an important geostrategic location, connecting East, South, West and Central Asia,[8] and has been home to various peoples through the ages. The region has been a target of various invaders since antiquity, including Alexander the Great, the Mauryan Empire, Muslim armies, and Genghis Khan, and has served as a source from which many kingdoms, such as the Greco-Bactrians, Kushans, Samanids, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, Timurids, and many others have risen to form empires of their own.[9]

The political history of modern Afghanistan begins in the 18th century with the rise of the Pashtun tribes (known as Afghans in Persian language), when in 1709 the Hotaki dynasty established its rule in Kandahar and, more specifically, when Ahmad Shah Durrani created the Durrani Empire in 1747 which became the forerunner of modern Afghanistan.[10][11][12] Its capital was shifted in 1776 from Kandahar to Kabul and most of its territories ceded to neighboring empires by 1893. In the late 19th century, Afghanistan became a buffer state in "The Great Game" between the British and Russian empires.[13] On August 19, 1919, following the third Anglo-Afghan war, the nation regained control over its foreign affairs from the British.

Since the late 1970s Afghanistan has experienced a continuous state of civil war punctuated by US secret aid to the opponents of the pro-Soviet afghan regime in 1979[14] and following 6 months later occupations in the forms of the 1979 Soviet invasion and the October 2001 US-led invasion that overthrew the Taliban government. In December 2001, the United Nations Security Council authorized the creation of an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to help maintain security and assist the Karzai administration. The country is being rebuilt slowly with support from the international community and dealing with Taliban insurgency.[15]

Contents |

Etymology

The name Afghānistān, Persian: افغانستان [avɣɒnestɒn],[16] means "Land of Afghans", from the word Afghan.

Origin of the name

The first part of the name, "Afghan", is, at least since the 16th century AD, the Persian alternative name for the Pashtuns who are the founders and the largest ethnic group of the country. According to W. K. Frazier Tyler, M. C. Gillet and several other scholars "the word Afghan first appears in history in the Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam in 982 AD." Al-Biruni referred to Afghans as various tribes living on the western frontier mountains of the Indus River, which would be the Sulaiman Mountains.[17]

The famous Moroccan travelling scholar, Ibn Battuta, visiting Kabul in 1333 writes:[18]

We travelled on to Kabul, formerly a vast town, the site of which is now occupied by a village inhabited by a tribe of Persians called Afghans.

However, it is unknown whether these historical Afghans were identical with the Pashtuns.[19] Summarizing the available information, the Encyclopædia Iranica states:[20]

From a more limited, ethnological point of view, "Afghān" is the term by which the Persian-speakers of Afghanistan (and the non-Paštō-speaking ethnic groups generally) designate the Paštūn. The equation [of] Afghan [and] Paštūn has been propagated all the more, both in and beyond Afghanistan, because the Paštūn tribal confederation is by far the most important in the country, numerically and politically.

It further explains:

The term "Afghān" has probably designated the Paštūn since ancient times. Under the form Avagānā, this ethnic group is first mentioned by the Indian astronomer Varāha Mihira in the beginning of the 6th century CE in his Brihat-samhita.

By the 17th century AD, it seems that some Pashtuns themselves began using the term as an ethnonym - a fact that is supported by traditional Pashto literature, for example, in the writings of the 17th-century Pashto poet Khushal Khan Khattak:[21]

Pull out your sword and slay any one, that says Pashtun and Afghan are not one! Arabs know this and so do Romans: Afghans are Pashtuns, Pashtuns are Afghans!

The last part of the name, -stān is an ancient Iranian languages suffix for "place", prominent in many languages of the region.

The term "Afghanistan", meaning the "Land of Afghans", was mentioned by the 16th century Mughal Emperor Babur in his memoirs, referring to the territories south of Kabul that were inhabited by Pashtuns (called "Afghans" by Babur).[22]

Until the 19th century the name was only used for the traditional lands of the Pashtuns, while the kingdom as a whole was known as the Kingdom of Kabul, as mentioned by the British statesman and historian Mountstuart Elphinstone.[23] Other parts of the country were at certain periods recognized as independent kingdoms, such as the Kingdom of Balkh in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[24]

With the expansion and centralization of the country, Afghan authorities adopted and extended the name "Afghanistan" to the entire kingdom, after its English translation had already appeared in various treaties between the British Raj and Qajarid Persia, referring to the lands subject to the Pashtun Barakzai Dynasty of Kabul.[25] "Afghanistan" as the name for the entire kingdom was mentioned in 1857 by Friedrich Engels.[26] It became the official internationally recognized name in 1919 after the Treaty of Rawalpindi was signed to regain full independence over its foreign affairs from the British,[27] and was confirmed as such in the nation's 1923 constitution.[28]

Geography

Afghanistan is variously described as being located within South Asia,[1][29] Central Asia,[30][31] and sometimes Western Asia (or the Middle East).[32] Afghanistan is landlocked and mountainous, with plains in the north and southwest. The highest point is Nowshak, at 7,485 m (24,557 ft) above sea level. The climate varies by region and tends to change quite rapidly. Large parts of the country are dry, and fresh water supplies are limited. The endorheic Sistan Basin is one of the driest regions in the world.[33]

Afghanistan has a continental climate with very harsh winters in the central highlands, the glaciated northeast (around Nuristan) and the Wakhan Corridor, where the average temperature in January is below −15 °C (5.0 °F), and hot summers in the low-lying areas of Sistan Basin of the southwest, the Jalalabad basin of the east, and the Turkistan plains along the Amu River of the north, where temperature averages over 35 °C (95 °F) in July. The country is frequently subject to minor earthquakes, mainly in the northeast of Hindu Kush mountain areas. Some 125 villages were damaged and 4,000 people killed by the May 31, 1998 earthquake.

At 249,984 sq mi (647,456 km2), Afghanistan is the world's 41st-largest country (after Burma). The nation shares borders with Pakistan in the southeast, Iran in the west, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in the north, and China in the far east. The country does not face any water shortage because it receives huge amount of snow during winter and once that melts the water runs into rivers, lakes, and streams, but most of its national water flows to neighboring states. The country needs around $2 billion to rehabilitate its irrigation systems so that the water is properly used.[34]

The country's natural resources include gold, silver, copper, zinc, and iron ore in the Southeast; precious and semi-precious stones (such as lapis, emerald, and azure) in the Northeast; and potentially significant petroleum and natural gas reserves in the North. The country also has uranium, coal, chromite, talc, barites, sulfur, lead, and salt.[35][36][37][38] However, these significant mineral and energy resources remain largely untapped due to the wars. In 2010, U.S. Pentagon and American geologists have revealed the discovery of about $1 trillion in untapped mineral deposits across Afghanistan[39] although the Afghan government insists that they are worth at least $3 trillion.[40][41]

History

| History of Afghanistan | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| See also | |||||||||||||||||

| Ariana · Khorasan | |||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | |||||||||||||||||

|

Pre-Islamic period

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Islamic conquest

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Modern history

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

Though the modern state of Afghanistan was established in 1747, the land has an ancient history and various timelines of different civilizations. Excavation of prehistoric sites by Louis Dupree, the University of Pennsylvania, the Smithsonian Institution and others suggest that humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago, and that farming communities of the area were among the earliest in the world.[42][43]

Afghanistan is a country at a unique nexus point where numerous civilizations have interacted and often fought, and was an important site of early historical activity. The region has been home to various peoples through the ages, among them were ancient Aryan tribes who established the dominant role of Indo-Iranian languages in the region. In certain stages of the history the land was conquered and incorporated within large empires, among them the Achaemenid Empire, the Macedonian Empire, the Indian Maurya Empire, the Muslim Arab Empire, the Sasanid Empire, and a number of others. Many dynasties and kingdoms have also risen to power in what is now Afghanistan, such as the Greco-Bactrians, Kushans, Indo-Sassanids, Kabul Shahis, Saffarids, Samanids, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, Kartids, Timurids, Mughals, and finally the Hotaki and Durrani dynasties that marked the political beginning of modern Afghanistan.

Pre-Islamic period

Archaeological exploration, which was done in the 20th century, suggests that the area of Afghanistan has been closely connected by culture and trade with the neighboring regions to the east, west, and north. Artifacts typical of the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron ages have been found in Afghanistan.[44] Urban civilization may have begun as early as 3000 BC, and the early city of Mundigak (near Kandahar in the south of the country) may have been a colony of the nearby Indus Valley Civilization.[43] After 2000 BCE, successive waves of semi-nomadic people from Central Asia moved south into the area of modern Afghanistan, among them were Indo-European-speaking Aryans (Indo-Iranians).[42] These tribes later migrated further south to India, west to what is now Iran, and towards Europe via north of the Caspian.[45] Since many of these settlers were Aryans (speakers of Indo-Iranian languages), the area was called Aryana, or Land of the Aryans.[42][46][47]

The ancient Zoroastrianism religion is believed by some to have originated in what is now Afghanistan between 1800 to 800 BCE, as its founder Zoroaster is thought to have lived and died in Balkh.[48][49][50] Ancient Eastern Iranian languages may have been spoken in the region around the time of the rise of Zoroastrianism. By the middle of the sixth century BCE, the Achaemenid Persian Empire overthrew the Medes and incorporated the region (known as Arachosia, Aria, and Bactria in Ancient Greek) within its boundaries. An inscription on the tombstone of King Darius I of Persia mentions the Kabul Valley in a list of the 29 countries he had conquered.[51]

Alexander the Great and his Macedonian (Greek) army arrived to the area of Afghanistan in 330 BCE after defeating Darius III of Persia a year earlier at the Battle of Gaugamela.[48] In a letter to his mother, Alexander described the inhabitants of what is now Afghanistan as lion-like brave people:[52]

I am involved in the land of a 'Leonine' (lion-like) and brave people, where every foot of the ground is like a well of steel, confronting my soldier. You have brought only one son into the world, but Everyone in this land can be called an Alexander.[52]

Following Alexander's brief occupation, the successor state of the Seleucid Empire controlled the area until 305 BCE when they gave much of it to the Indian Maurya Empire as part of an alliance treaty. The Mauryans brought Buddhism from India and controlled southern Afghanistan until about 185 BCE when they were overthrown.[53] Their decline began 60 years after Ashoka's rule ended, leading to the Hellenistic reconquest of the region by the Greco-Bactrians. Much of it soon broke away from the Greco-Bactrians and became part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The Indo-Greeks were defeated and expelled by the Indo-Scythians by the end of the 2nd century BCE.

During the first century, the Parthian Empire subjugated the region, but lost it to their Indo-Parthian vassals. In the mid to late 1st century CE the vast Kushan Empire, centered in modern Afghanistan, became great patrons of Buddhist culture. The Kushans were defeated by the Sassanids in the third century. Although various rulers calling themselves Kushanshas (generally known as Indo-Sassanids) continued to rule at least parts of the region, they were probably more or less subject to the Sassanids.[54] The late Kushans were followed by the Kidarite Huns[55] who, in turn, were replaced by the short-lived but powerful Hephthalites, as rulers of the region in the first half of the fifth century.[56] The Hephthalites were defeated by the Sasanian king Khosrau I in CE 557, who re-established Sassanid power in Persia. However, in the 6th century CE, the successors of Kushans and Hepthalites established a small dynasty in Kabulistan called Kabul Shahi.

Islamic conquests and Mongol invasion

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, most of the region was recognized as Khorasan.[57][58] Several important centers of Khorasan are thus located in modern Afghanistan, such as Herat and Balkh. In some cases even the cities of Kandahar, Ghazni and Kabul were recognized as the frontier cities of Khorasan. However, the area which was inhabited by the Afghan tribes (Pashtuns) was referred to as Afghanistan.

During the 7th century, Arabs brought the religion of Islam to the western area of Afghanistan and began spreading eastward. Although some accepted the new religion, others revolted and quickly went back to their old pre-Islamic way of life. Prior to the introduction of Islam, the area of Afghanistan was inhabited by people of various religious backgrounds, which included Zoroastrians, Hindus, Buddhists, Shamanists, Jews, and others. The Kabul Shahis began losing control of their territories to the Muslim Arabs, and their Kabul capital was conquered by the Saffarids in 879. The Samanids extended their influence to Khorasan and south into parts of the Afghan tribal areas in the 9th century, and by the late-10th century the Ghaznavids had made all of the remaining non-Muslim territories convert to Islam, with the exception of the Kafiristan region. Afghanistan at that point became the center of many important empires such as the Saffarids of Zaranj, Samanids of Balkh,[59][60] Ghaznavids of Ghazni, Ghurids of Ghor, and Timurids of Herat.

The region was overrun in 1219 by Genghis Khan and his Mongol army, who devastated much of the land. For example, his troops are said to have annihilated the ancient Khorasan cities of Herat and Balkh.[61] The destruction caused by the Mongols depopulated major cities and caused much of the locals to revert to an agrarian rural society.[62] Their rule continued with the Ilkhanate, and was extended further following the invasion of Timur (Timur-lang) who established the Timurid dynasty.[63] The periods of the Ghaznavids,[64] Ghurids, and Timurids are considered some of the most brilliant eras of Afghanistan's history because they produced fine Islamic architectural monuments[42] as well as numerous scientific and literary works.

Babur, a descendant of both Timur and Genghis Khan, arrived from Central Asia and captured Kabul from the Arghun Dynasty, and from there he began to seize control of the rest of today's eastern Afghan territories. He remained in Kabul until 1526 when he along with his army invaded India to sack its capital, Delhi, and establish the Mughal Empire. From the 16th century to the early 18th century, the region of Afghanistan was contended by 3 major powers: The Khanate of Bukhara ruled the north, Safavid Persians the west and the remaining larger area was ruled by the Mughals.

Hotaki dynasty and the Durrani Empire

Mir Wais Hotak, an influential Afghan tribal leader of the Ghilzai tribe, gathered supporters and successfully rebelled against the Persian Safavids in the early 1700s. Mirwais Khan overthrew and killed Gurgin Khan, the Safavid governor of Kandahar, and made the Afghan region independent. By 1713, Mirwais had decisively defeated two larger Persian-Georgian armies, one was led by Khusraw Khán (nephew of Gurgin) and the other by Rustam Khán. The armies were sent by Soltan Hosein, the Safavid King from Isfahan (now Iran), to re-take control of the Kandahar region. Mirwais died of a natural cause in 1715 and his son, Mahmud, took over. In 1722, Mahmud led an Afghan army to the Persian capital of Isfahan, sacked the city during the Battle of Gulnabad and proclaimed himself King of Persia. The Persians refused to recognize the Afghan ruler, and after the massacre of thousands of Persian religious scholars, nobles, and members of the Safavid family, the Hotaki dynasty was eventually ousted from Persia during the Battle of Damghan.[65][66]

In 1738, Nader Shah and his army, which included Ahmad Khan and four thousand of his Abdali Pashtuns,[67] captured Kandahar from the last Hotak ruler; in the same year he occupied Ghazni, Kabul and Lahore. In June 1747, Nadir Shah was assassinated by one of his officers[68][69] and his kingdom fell apart. Ahmad Shah Abdali called for a loya jirga ("grand assembly") to select a leader among his people, and in October 1747 the Pashtuns gathered near Kandahar and chose him as their new head of state. Ahmad Shah Durrani is often regarded as the founder of modern Afghanistan.[1][70][71] After the inauguration, Ahmad Shah adopted the title padshah durr-i dawran ('King, "pearl of the age")[72] and the Abdali tribe became known as the Durrani tribe there after.

By 1751, Ahmad Shah Durrani and his Afghan army conquered the entire present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, Khorasan and Kohistan provinces of Iran, along with Delhi in India.[26] He defeated the Sikhs of the Maratha Empire in the Punjab region nine times, one of the biggest battles was the 1761 Battle of Panipat. In October 1772, Ahmad Shah retired to his home in Kandahar where he died peacefully and was buried there at a site that is now adjacent to the Mosque of the Cloak of the Prophet Mohammed. He was succeeded by his son, Timur Shah Durrani, who transferred the capital of their Afghan Empire from Kandahar to Kabul. Timur died in 1793 and was finally succeeded by his son Zaman Shah Durrani.

Zaman Shah and his brothers had a weak hold on the legacy left to them by their famous ancestor. They sorted out their differences through a "round robin of expulsions, blindings and executions", which resulted in the deterioration of the Afghan hold over far-flung territories, such as Attock and Kashmir.[73] Durrani's other grandson, Shuja Shah Durrani, fled the wrath of his brother and sought refuge with the Sikhs.

After he was defeated at the Battle of Attock, Durrani Vizier Fateh Khan fought off an attempt by Ali Shah, the ruler of Persia, to capture the Durrani province of Herat. He was joined by his brother, Dost Mohammad Khan, and rogue Sikh Sardar Jai Singh Attarwalia. Once they had captured the city, Fateh Khan attempted to remove the ruler, a relation of his superior, Mahmud Shah, and rule in his stead. In the attempt to take the city from its Durrani ruler, Dost Mohammad Khan's men forcibly took jewels off of a princess and Kamran Durrani, Mahmud Shah's son, used this as a pretext to remove Fateh Khan from power, and had him tortured and executed. While in power, however, Fateh Khan had installed 21 of his brothers in positions of power throughout the Durrani Empire. After his death, they rebelled and divided up the provinces of the empire between themselves. During this turbulent period Kabul had many temporary rulers until Fateh Khan's brother, Dost Mohammad Khan, captured Kabul in 1826.

The Sikhs, under Ranjit Singh, rebelled in 1809 and eventually wrested a large part of the Kingdom of Kabul (present day Pakistan, but not including Sindh) from the Afghans.[74] Hari Singh Nalwa, the Commander-in-Chief of the Sikh Empire along its Afghan frontier, invaded the Afghan territory as far as the city of Jalalabad.[75] In 1837, the Afghan Army descended through the Khyber Pass on Sikh forces at Jamrud. Hari Singh Nalwa's forces held off the Afghan offensive for over a week – the time it took reinforcements to reach Jamrud from Lahore.[76]

Barakzai dynasty and European influence

During the 19th century, following the Second Anglo-Afghan War and the ascension of the Barakzai dynasty, Afghanistan saw much of its territory and autonomy ceded to British India. Ethnic Pashtun territories were divided by the 1893 Durand Line, which would lead to strained relations between Afghanistan and British India (later the new state of Pakistan). The United Kingdom exercised a great deal of influence, and it was not until the reign of King Amanullah Khan in 1919 that Afghanistan re-gained independence over its foreign affairs after the Treaty of Rawalpindi was signed.

King Amanullah moved to end his country's traditional isolation in the years following the Third Anglo-Afghan War. He established diplomatic relations with major states and, following a 1927-28 tour of Europe and Turkey, introduced several reforms intended to modernize his nation. A key force behind these reforms was Mahmud Tarzi, an ardent supporter of the education of women. He fought for Article 68 of Afghanistan's first constitution (declared through a Loya Jirga), which made elementary education compulsory.[77] Some of the reforms that were actually put in place, such as the abolition of the traditional Muslim veil for women and the opening of a number of co-educational schools, quickly alienated many tribal and religious leaders. Faced with overwhelming armed opposition, Amanullah Khan was forced to abdicate in January 1929 after Kabul fell to rebel forces led by Habibullah Kalakani. Prince Mohammed Nadir Shah, Amanullah's cousin, in turn defeated and killed Habibullah Kalakani in October 1929, and was declared King Nadir Shah. He abandoned the reforms of Amanullah Khan in favor of a more gradual approach to modernisation. In 1933, however, he was assassinated in a revenge killing by a Kabul student.

Mohammed Zahir Shah, Nadir Shah's 19-year-old son, succeeded to the throne and reigned from 1933 to 1973. Until 1946 Zahir Shah ruled with the assistance of his uncle, who held the post of Prime Minister and continued the policies of Nadir Shah. Another of Zahir Shah's uncles, Shah Mahmud Khan, became Prime Minister in 1946 and began an experiment allowing greater political freedom, but reversed the policy when it went further than he expected. In 1953, he was replaced by Mohammed Daoud Khan, the king's cousin and brother-in-law. Daoud sought a closer relationship with the Soviet Union and a more distant one towards Pakistan. Afghanistan remained neutral and was not a participant in World War II, nor aligned with either power bloc in the Cold War. However, it was a beneficiary of the latter rivalry as both the Soviet Union and the United States vied for influence by building Afghanistan's main highways, airports and other vital infrastructure. By the late 1960s many western travelers were using these as part of the hippie trail. In 1973, Zahir Shah's brother-in-law, Mohammed Daoud Khan, launched a bloodless coup and became the first President of Afghanistan while Zahir Shah was on an official overseas visit.

Saur revolution and Soviet war

In 1978, a prominent member of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), Mir Akbar Khyber, was killed by the government. Leaders of the PDPA feared that Daoud was planning to dismantle them because many were being arrested. Hafizullah Amin along with other PDPA members managed to remain at large and organised an uprising.

.jpg)

The PDPA, led by Nur Mohammad Taraki, Babrak Karmal and Hafizullah Amin, overthrew the regime of Mohammad Daoud, who was assassinated along with his family during the April 1978 Saur Revolution. Few days later Taraki became President, Prime Minister and General Secretary of the PDPA. Once in power, the PDPA implemented a socialist agenda. It moved to promote state atheism,[78] and carried out an ill-conceived land reform, which were misunderstood by virtually all Afghans.[79] They also imprisoned, tortured or murdered thousands of members of the traditional elite, the religious establishment, and the intelligentsia.[79] They also prohibited usury[80] and made a number of statements on women's rights, by declaring equality of the sexes[80] and introduced women to political life. A prominent example was Anahita Ratebzad, who was a major Marxist leader and a member of the Revolutionary Council.[81]

As part of a Cold War strategy, in 1979 the United States government began to covertly fund Mujahideen forces against the pro-Soviet government, although warned that this might prompt a Soviet intervention, according to President Jimmy Carter's National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski. The Mujahideen belonged to various different factions, but all shared, to varying degrees, a similarly conservative 'Islamic' ideology. In March 1979 Hafizullah Amin took over as prime minister, retaining the position of field marshal and becoming vice-president of the Supreme Defence Council. Taraki remained President and in control of the army until September 14 when he was killed.

To bolster the Parcham faction, the Soviet Union decided to intervene on December 24, 1979, when the Red army invaded its southern neighbor. Over 100,000 Soviet troops took part in the invasion backed by another one hundred thousand Afghan military men and supporters of the Parcham faction. In the meantime, Hafizullah Amin was killed and replaced by Babrak Karmal. In response to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and part of its overall Cold War strategy, the Reagan administration in the U.S. increased arming and funding of the Mujahideen who began a gurella war. Thanks in large part to the efforts of Texas Congressman Charlie Wilson and CIA officer Gust Avrakotos, the US supplied several hundred FIM-92 Stinger surface-to-air missiles to the Mujahideen during the 1980s for the purpose of defending against Soviet helicopters. The U.S. handled its support through its middlemen Pakistan's ISI. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia was providing some financial support to factions that belonged to Jalaluddin Haqqani, Gulbadin Hekmatyar and others. Leaders such as Ahmad Shah Massoud also received support, he was seen by some analysts as the most famous resistance leader, who fought back nine major offensives by the Soviet army in his home region of Panjshir.[82]

The 10-year Soviet occupation resulted in the killings of between 600,000 and two million Afghans, mostly civilians.[83] About 6 million fled as Afghan refugees to Pakistan and Iran, and from there over 38,000 made it to the United States[84] and many more to the European Union. Faced with mounting international pressure and great number of casualties on both sides, the Soviets withdrew in 1989. Their withdrawal from Afghanistan was seen as an ideological victory in America, which had backed some Mujahideen factions through three U.S. presidential administrations to counter Soviet influence in the vicinity of the oil-rich Persian Gulf. The USSR continued to support President Mohammad Najibullah (former head of the Afghan secret service, KHAD) until 1992.[85]

Civil war

After the fall of the communist Najibullah-regime in 1992, the Afghan political parties agreed on a peace and power-sharing agreement (the Peshawar Accords). The Peshawar Accords created the Islamic State of Afghanistan and appointed an interim government for a transitional period. Human Rights Watch writes: "The sovereignty of Afghanistan was vested formally in "The Islamic State of Afghanistan", an entity created in April 1992, after the fall of the Soviet-backed Najibullah government. ... With the exception of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, all of the parties ... were ostensibly unified under this government in April 1992. ... Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, for its part, refused to recognize the government for most of the period discussed in this report and launched attacks against government forces and Kabul generally. ... Hekmatyar continued to refuse to join the government. Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami forces increased their rocket and shell attacks on the city. Shells and rockets fell everywhere."[86] Gulbuddin Hekmatyar was directed, funded and supplied by the Pakistani army. Amin Saikal concludes in his book which was chosen by The Wall Street Journal as 'One of the "Five Best" Books on Afghanistan': "Pakistan was keen to gear up for a breakthrough in Central Asia. ... Islamabad could not possibly expect the new Islamic government leaders, especially Massoud (who had always maintained his independence from Pakistan), to subordinate their own nationalist objectives in order to help Pakistan realize its regional ambitions. ... Had it not been for the ISI's logistic support and supply of a large number of rockets, Hekmatyar's forces would not have been able to target and destroy half of Kabul."[87] Saudi Arabia and Iran also armed and directed their respective proxy Afghan militias. A publication with the George Washington University describes: "[O]utside forces saw instability in Afghanistan as an opportunity to press their own security and political agendas."[88] According to Human Rights Watch, numerous Iranian agents were assisting Hezb-i Wahdat forces, as Iran was attempting to maximize Wahdat's military power and influence in the new government.[86] Saudi agents of some sort, private or governmental, were trying to strengthen Sayyaf and his Ittihad-i Islami faction to the same end.[86] Rare ceasefires, usually negotiated by representatives of Massoud, Mujaddidi or Rabbani, or officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), commonly collapsed within days.[86]

Taliban and Northern Alliance

Hekmatyar's failure to achieve what was expected of him prompted the Pakistani intelligence service ISI leaders to come up with a new surrogate force: the Taliban.[87] The Taliban developed as a politico-religious force in 1994, eventually seizing Kabul in 1996 and establishing the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The Taliban imposed on the parts of Afghanistan under their control their Wahhabi interpretation of Islam. See an analysis by the Physicians for Human Rights.

After the fall of Kabul to the Taliban on September 27, 1996,[89] Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rashid Dostum, one of his former archnemesis, for the survival of their remaining territories were forced to create an alliance against the Taliban, Pakistan and Al Qaeda which were about to attack the areas of Massoud and those of Dostum. The alliance was called United Front but in the Western and Pakistani media became known as the Northern Alliance. In the following years many more were to join the United Front. These included Afghans and Afghan commanders from all regions and Afghan ethnicities including Tadjiks, Hazara, Usbeks and many Pashtuns such as Commanders Abdul Haq, Haji Abdul Qadir and Qari Baba, or diplomat Abdul Rahim Ghafoorzai. As the Taliban committed massacres, especially among the Shia and Hazara population which they regarded as "sub-humans" worse than "non-believers" an thus according to them were without any rights many people fled to the area of Massoud. The National Geographic concluded: "The only thing standing in the way of future Taliban massacres is Ahmad Shah Massoud."[90] Massoud also set up democratic institutions including political, economic, health and education committees and signed the Women's Rights Charta.[91]

Pervez Musharraf - then as Chief of Army Staff - was responsible for sending scores of regular Pakistani army troops to fight alongside the Taliban and Bin Laden against Ahmad Shah Massoud.[90][92] In total there were believed to be 28 000 Pakistani nationals fighting alongside the Taliban.[91] From 1996 to 2001 Osama Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri became a virtual state within the Taliban state. Bin Laden sent Arab fighters to join the fight against the United Front[82][93], especially his so-called Brigade 055, which was also responsible for massacres.[94]

NATO mission in Afghanistan

Following the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, the U.S. and British air forces began bombing al-Qaeda and Taliban targets inside Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom.[95] On the ground, American and British special forces along with CIA Special Activities Division units worked with commanders of the Northern Alliance to launch a military offensive against the Taliban forces.[96] These attacks led to the fall of Mazar-i-Sharif and Kabul in November 2001, as the Taliban retreated from the north of the country to the south. In December 2001, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was established by the UN Security Council to help assist the newly formed Karzai administration.[97]

As more coalition troops entered the war and the Northern Alliance made their way southwards, the Taliban and al-Qaida retreated toward the mountainous Durand Line border between Afghanistan and Pakistan.[98] From 2002 onward, the Taliban focused on survival and on rebuilding its forces. Meanwhile, NATO assumed control of ISAF in 2003[99] and the rebuilding of Afghanistan began, which is funded by the United States and many other nations. Over the course of the years, NATO and Afghan troops led several offensives against the entrenched Taliban, but proved unable to completely dislodge their presence. By 2009, a Taliban-led shadow government began to form complete with their own version of mediation court.[100]

In 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama deployed an additional 30,000 soldiers over a period of six months and proposed that he will begin troop withdrawals by 2012. At the 2010 International Conference on Afghanistan in London, Afghan President Hamid Karzai told world leaders that he intends to reach out to the top echelons of the Taliban with a peace initiative. Karzai set the framework for dialogue with Taliban when he called on the group's leadership to take part in a loya jirga (grand assembly) to initiate peace talks. The Afghan nation is currently struggling to rebuild itself while dealing with Taliban insurgency and political corruption within the government.

Government and politics

Politics in Afghanistan has historically consisted of power struggles, bloody coups and unstable transfers of power. With the exception of a military junta, the nation has been governed by nearly every system of government over the past centuries, including a monarchy, republic, theocracy and communist state. The constitution ratified by the 2003 Loya jirga restructured the government as an Islamic republic consisting of three branches, executive, legislative and judicial.

The nation is currently led by the Karzai administration with Hamid Karzai as the President and leader since December 20, 2001. The current parliament was elected in 2005, and among the elected officials were former mujahideen, Islamic fundamentalists, communists, reformists, and Taliban members. 28% of the delegates elected were women, three points more than the 25% minimum guaranteed under the constitution. This made Afghanistan, long known under the Taliban for its oppression of women, 30th amongst nations in terms of female representation.[101] Construction for a new parliament building began on August 29, 2005.

The Supreme Court of Afghanistan is currently led by Chief Justice Abdul Salam Azimi, a former university professor who had been legal advisor to the president.[102] The previous court, appointed during the time of the interim government, had been dominated by fundamentalist religious figures, including Chief Justice Faisal Ahmad Shinwari. The court issued several rulings, such as banning cable television, seeking to ban a candidate in the 2004 presidential election and limiting the rights of women, as well as overstepping its constitutional authority by issuing rulings on subjects not yet brought before the court. The current court is seen as more moderate and led by more technocrats than the previous court.

Elections and parties

The 2004 Afghan presidential election went relatively smooth in which Hamid Karzai won in the first round with 55.4% of the votes. However, the 2009 presidential election was characterized by lack of security, low voter turnout and widespread electoral fraud.[103][104][105] The vote, along with elections for 420 provincial council seats, took place in August 2009, but remained unresolved during a lengthy period of vote counting and fraud investigation.[106]

Two months later, under U.S. and ally pressure, a second round run-off vote between Karzai and remaining challenger Abdullah was announced for November 7, 2009, but on the 1st of November Abdullah announced that he would no longer be participating in the run-off because his demands for changes in the electoral commission had not been met, and claiming a transparent election would not be possible. A day later, officials of the election commission cancelled the run-off and declared Hamid Karzai as President of Afghanistan for another 5 year term.[104][105]

The Afghan government ranks as one of the top corrupted administrations in the world. In November 2009, Afghanistan slipped three places in Transparency International's annual index of corruption perceptions, becoming the world's second most-corrupt country.[107] A number of government ministries are believed to be rife with corruption, including the Interior, Education and Health. President Karzai vowed to tackle the problem in November 2009, he stated that "individuals who are involved in corruption will have no place in the government."[108] A January 2010 report published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime revealed that bribery consumes an amount equal to 23 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the nation. Citizens are forced by corrupt government culture to pay more than a third of their income in bribes.[109]

Political divisions

Afghanistan is administratively divided into 34 provinces (wilayats), with each province having a capital and a governor in office. The provinces are further divided into about 398 smaller provincial districts and each of the districts normally covers a city or a number of villages. Each provincial district is represented by a sub-governor, usually called a district governor.

The provincial governors as well as the district governors are voted into office during the nation's presidential election, which takes place every five years. The provincial governors are representatives of the central government in Kabul and are responsible for all administrative and formal issues within their provinces. The provincial Chief of Police is appointed by the Ministry of Interior in Kabul and works together with the provincial governor on law enforcement for all the districts within the province.

There is an exception in the capital city of Kabul where the Mayor is selected directly by the President, and is completely independent from the Governor of Kabul.

The following is a list of all the 34 provinces of Afghanistan in alphabetical order and on the right is a map showing where each province is located:

Foreign relations and military

The Afghan Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for managing the foreign relations of Afghanistan. The nation has maintained good relations with the United States and other members of NATO since at least the 1920s. Afghanistan joined the United Nations on November 19, 1946, and has been a member since. In 2002, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan was established to help rebuild the country. Today, more than 22 NATO nations deploy over 100,000 troops in Afghanistan as a part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). Apart from close military links, Afghanistan also enjoys strong economic relations with NATO members and other allies. The United States is the largest donor to Afghanistan, followed by Japan, United Kingdom, Germany, India and others.[110]

Relations between Afghanistan and neighboring Pakistan often fluctuate and tensions between the two countries have existed since 1947.[111][112][113] During the Taliban 1996 to 2001 rule, Pakistan was supporting the Taliban leaders[114] against the Iranian-backed Northern Alliance.[115] Though Pakistan maintains strong security and economic links with Afghanistan, dispute between the two countries remain due to Pakistani concerns over growing influence of rival India in Afghanistan and the continuing border dispute over the poorly-marked Durand Line.[116]

In May 2007, Afghan and Pakistani forces became involved in border skirmishes. Relations between the two strained further after Afghan officials alleged that Pakistani intelligence agencies were involved in some terrorist attacks on Afghanistan.[117][118] Pakistan is a participant in the reconstruction of Afghanistan, pledging $250 million in various projects across the country.[119]

Afghanistan has close historical, linguistic and cultural ties with neighboring Iran as both countries were part of Greater Persia before 1747.[120] Afghanistan-Iran relations formally initiated after 1935 between Zahir Shah and Reza Shah, which soured after the rise of radical Sunni Taliban regime in 1997 but rebounded after the establishment of Karzai government.[121] Iran has also actively participated in the Afghan reconstruction efforts[122] but is accused at the same time by American and British politicians of secretly funding the Taliban against NATO-Afghan officials.[123] Afghanistan also enjoys good relations with neighboring Central Asian nations, especially Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

India is often regarded as one of Afghanistan's most influential allies.[124] India is the largest regional donor to Afghanistan and has extensively participated in several Afghan reconstruction efforts, including power, agricultural and educational projects.[125][126] Since 2002, India has extended more than US$1.2 billion in aid to Afghanistan.[127] Strong military ties also exist – Afghan security forces regularly get counter-insurgency training in India[128] and India is also considering the deployment of troops in Afghanistan.[129]

The military of Afghanistan is under the Ministry of Defense, which includes the Afghan National Army and the Afghan National Army Air Force. It currently has about 134,000 members and is expected to reach 260,000 in the coming years. They are trained and equipped by NATO countries, mainly by the United States armed forces. The ANA is divided into 7 major Corps, with the 201st Selab ("Flood") in Kabul being the main one. The ANA also has a special commando brigade which was started in 2007. The National Military Academy of Afghanistan serves as the main education institute for the militarymen of the country. A new $200 million Afghan Defense University (ADU) is under construction near the capital.

Economy

Afghanistan is a member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) and the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC). It is an impoverished country, one of the world's poorest and least developed. As of 2008, the nation's unemployment rate is 35%[130] and roughly 36% of its citizens live below the poverty line.[131] Two-thirds of the population live on fewer than 2 US dollars a day. The nation's economy has suffered greatly from the 1978 to 2001 conflicts, while severe drought added to the nation's difficulties in 1998–2001.[132]

However, due to the infusion of multi-billion dollars in international assistance and investments, as well as remittances from expats[133], the economy of this war-torn country is slowly improving. It is also due to improvements in agricultural production, which is the backbone of the nation's economy since nearly 80% of its citizens are involved with this line of work.[134] Afghanistan is known for producing some of the finest pomegranates, grapes, apricots, melons, and several other fresh and dry fruits, including nuts.[135] According to the World Bank, "economic growth has been strong and has generated better livelihoods" since late 2001.[136]

As much as one-third of the nations's GDP comes from growing illicit drugs, including hashish and opium. Opium production in Afghanistan has soared to a record in 2007 with some 3.3 million Afghans reported to be involved in the business.[137] However, it began declining significantly in the next few years.[138] The Afghan government began programs to reduce the cultivation of poppy and by 2010 it was reported that 24 out of the 34 provinces are free from poppy cultivation.

One of the main drivers for the current economic recovery is the return of over 5 million Afghan refugees from neighbouring countries, who brought with them fresh energy, entrepreneurship and wealth-creating skills as well as much needed funds to start up businesses. Afghan rugs have become a popular product again and this gives the large number of rug weavers in the country a chance to earn more income. While the country's current account deficit is largely financed with the donor money, only a small portion – about 15% – is provided directly to the government budget. The rest is provided to non-budgetary expenditure and donor-designated projects through the United Nations system and non-governmental organizations.

The country's foreign exchange reserves total about $3.781 billion as of March 2010.[139] The Afghan Ministry of Finance is focusing on improved revenue collection and public sector expenditure discipline. The rebuilding of the financial sector seems to have been so far successful. Since 2003, over sixteen new banks have opened in the country, including Afghanistan International Bank, Kabul Bank, Azizi Bank, Pashtany Bank, Standard Chartered Bank, First Micro Finance Bank, and others. However, in early September 2010, one of the principal owners of the Kabul Bank, at the center of an accelerating financial crisis in Afhganistan, said depositors had withdrawn $180 million in the past two days. He predicted a "revolution" in the country's financial system unless the Afghan government and the United States moved quickly to help stabilize the bank.[140] Da Afghanistan Bank serves as the central bank of the nation and the "Afghani" (AFN) is the national currency, which has been performing steadily for the last eight years with an exchange rate of about 45 Afghanis to 1 US dollar.

Energy and mining

According to recent U.S. Geological Surveys that were funded by the Afghan Ministry of Mines and Industry, Afghanistan may be possessing up to 36 trillion cubic feet (1,000 km3) of natural gas, 3.6 billion barrels (570,000,000 m3) of petroleum and up to 1,325 million barrels (210,700,000 m3) of natural gas liquids.[141] Other recent reports show that the country has huge amounts of gold, copper, coal, iron ore and other minerals.[36][142][143] In 2010, U.S. Pentagon officials along with American geologists revealed the discovery of nearly $1 trillion in untapped mineral deposits in Afghanistan.[39]

Afghan officials assert that "this will become the backbone of the Afghan economy" and a memo from the Pentagon stated that Afghanistan could become the "Saudi Arabia of lithium".[144] Some believe, including Afghan President Hamid Karzai, that the untapped minerals could be as high as $3 trillion.[145][146][147] The government of Afghanistan is preparing deals to extract its copper and iron reserves, which will earn billions of dollars in royalties and taxes every year for the next 100 years.[148][149] These untapped resources could mark the turning point in Afghanistan's reconstruction efforts. Energy and mineral exports could generate the revenue that Afghan officials need to modernize the country's infrastructure, and expand economic opportunities for the beleaguered and fractious population.

Transport and communications

Ariana Afghan Airlines is the national airlines carrier, with domestic flights between Kabul, Kandahar, Herat and Mazar-e Sharif. International flights include to Dubai, Frankfurt, Istanbul and a number of other Asian destinations.[150] There are also limited domestic and international flight services available from the locally owned Kam Air, Pamir Airways and Safi Airways.

The country has limited rail service with Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan in the north. There are two other railway projects currently in progress with neighboring nations, one is between Herat and Iran while another is to connect with Pakistan Railways.

Most citizens who travel far distances use long traveling bus services. Newer automobiles have recently become more widely available after the rebuilding of roads and highways. Vehicles are imported from the United Arab Emirates through Pakistan and Iran. Postal and package delivery services such as FedEx, DHL and others exist in major cities and towns.

Telecommunication services in the country are provided by Afghan Wireless, Etisalat, Roshan, Areeba and Afghan Telecom. In 2006, the Afghan Ministry of Communications signed a 64.5 million agreement with ZTE Corporation for the establishment of a countrywide optical fiber cable network.[151] As of 2008, the country has 460,000 telephone lines[152], 8.45 million mobile phone users[153] and around 500,000 people (1.5% of the population) have internet access.[154]

Demographics

A 2009 UN estimate shows that the Afghan population is 28,150,000,[2] with about 2.7 million Afghan refugees currently staying in neighoboring Pakistan and Iran.[155] A 2009–2010 survey conducted by the Central Statistics Office (CSO) of Afghanistan has put the population at 26 million but not counting some parts of the country due to insecurity.[156]

A partial census conducted in 1979 showed around 13,051,358 people living in the country. By 2050, the population is estimated to increase to 82 million.[157]

The only city in Afghanistan with over one million residents is its capital, Kabul. The other major cities in the country are, in order of population size, Kandahar, Herat, Mazar-e Sharif, Jalalabad, Ghazni and Kunduz. Urban areas are experiencing rapid population growth following the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 2002, which is mainly due to the return of over 5 million former refugees from Pakistan and Iran.

Ethnic groups

The population of Afghanistan is divided into a wide variety of ethnic groups. Because a systematic census has not been held in the country in decades, exact figures about the size and composition of the various ethnic groups are not available.[158] In this regard, the Encyclopædia Britannica states:

No national census has been conducted in Afghanistan since a partial count in 1979, and years of war and population dislocation have made an accurate ethnic count impossible. Current population estimates are therefore rough approximations, which show that Pashtuns comprise somewhat less than two-fifths of the population. The two largest Pashtun tribal groups are the Durrānī and Ghilzay. Tajiks are likely to account for some one-fourth of Afghans and Ḥazāra nearly one-fifth. Uzbeks and Chahar Aimaks each account for slightly more than 5 percent of the population and Turkmen an even smaller portion.[159]

The following are approximation figures provided by other sources:

|

(1) Based on official census numbers from the 1960s to the 1980s, as well as information found in mainly scholarly sources, the Encyclopædia Iranica[160] gives the following list: |

(2) An approximate distribution of ethnic groups based on the CIA World Factbook[1] is as following:

|

|

(3) According to a representative survey, named "A survey of the Afghan people – Afghanistan in 2006", a combined project of The Asia Foundation, the Indian Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) and the Afghan Center for Socio-economic and Opinion Research (ACSOR), the distribution of the ethnic groups is:[161]

|

(4) According to another representative survey, named "Afghanistan: Where Things Stand", a combined effort by the American broadcasting channel ABC News, the British BBC, and the German ARD (from the years 2004 to 2009), and released on February 9, 2009, the ethnic composition of the country is (average numbers):[162]

|

Languages

The most common languages spoken in Afghanistan are Pashto and Persian (officially known as Dari), both Indo-European languages from the Iranian languages sub-family, and the official languages of the country. Other languages, such as Uzbek, Turkmen, Pashayi, are spoken by minorities across the country, and have official status in the regions where they are the language of the majority. An approximate distribution of languages based on the CIA World Factbook is as following:[1]

- Pashto: 66%

- Dari: 30%

- Turkic languages (primarily Uzbek and Turkmen): 8%

- 30 minor languages (primarily Balochi and Pashayi): 4%

- much bilingualism

Other minor languages include Nuristani (Ashkunu, Kamkata-viri, Vasi-vari, Tregami and Kalasha-ala), Pamiri (Shughni, Munji, Ishkashimi and Wakhi), Brahui, Hindko, Kyrgyz, etc.

According to older numbers in the Encyclopædia Iranica,[164] the Persian language is spoken by percent of the population (although ca. 25% native), while Pashto is spoken and understood by around 60% of the population (50–55% native). According to "A survey of the Afghan people – Afghanistan in 2006",[161] Persian is the first language of 49% of the population, while additional 37% speak the language as a second language (combined 86%). Pashto is the first language of 40% of the population, while additional 27% know the language (combined 67%). Uzbek is spoken or understood by 6% of the population, Turkmen by 3%. In the survey "Afghanistan: Where Things Stand" (average numbers from 2005 to 2009), 69% of the interviewed people preferred Persian, while 31% preferred Pashto. Additionally, 45% of the polled people said that they can read Persian, while 36% said that they can read Pashto.[162]

Religions

Religiously, Afghans are over 99% Muslims: approximately 80% Sunni, 19% Shi'a, and 1% other.[1] Until the 1890s, the region around Nuristan was known as Kafiristan (land of the kafirs) because of its inhabitants: the Nuristani, an ethnically distinctive people who practiced animism, polytheism and shamanism.[165]

Up until the mid-1980s, there were possibly about 50,000 Hindus and Sikhs living in different cities, mostly in Kabul, Kandahar, Jalalabad, and Ghazni.[166][167]

There was also a small Jewish community in Afghanistan who emigrated to Israel and the United States by the end of the last century, and only one individual, Zablon Simintov, remains today.[168]

Health and education

According to the Human Development Index, Afghanistan is the second least developed country in the world.[169] Every half hour, an average of one woman dies from pregnancy-related complications, another dies of tuberculosis and 14 children die, largely from preventable causes. Before the start of the wars in 1978, the nation had an improving health system and a semi-modernized health care system in cities like Kabul. Ibn Sina Hospital and Ali Abad Hospital in Kabul were two of the leading health care institutions in Central Asia at the time.[170] Following the Soviet invasion and the civil war that followed, the health care system was limited only to urban areas and was eventually destroyed.

The Taliban government made some improvements in the late 1990s, but health care was not available for women during their six year rule.[170] After the removal of the Taliban in late 2001, the humanitarian and development needs in Afghanistan remain acute.[171] After about 30 years of non-ending war, there are an estimated one million disabled or handicapped people in the country.[172] An estimated 80,000 citizens of the country have lost limbs, mainly as a result of landmines.[173] This is one of the highest percentages anywhere in the world.[174]

The nation's health care system began to improve dramatically since 2002, which is due to international support on the vaccination of children, training of medical staff, and all institutions allowing women for the first time since 1996. Many new modern hospitals and clinics are being built across the country during the same time, which are equipped with latest medical equipments. Non-governmental charities such as Mahboba's promise assist orphans in association with governmental structures.[175] According to Reuters, "Afghanistan's healthcare system is widely believed to be one of the country's success stories since reconstruction began."[170] However, in November 2009, UNICEF reported that Afghanistan is the most dangerous place in the world for a child to be born.[176] The nation has the highest infant mortality rate in the world – 257 deaths per 1,000 live births – and 70 percent of the population lacks access to clean water.[177][178] The Afghan Ministry of Public Health has ambitious plans to cut the infant mortality rate to 400 from 1,600 for every 100,000 live births by 2020.[170]

One of the oldest schools in the country is the Habibia High School in Kabul. It was established by King Habibullah Khan in 1903 and helped educate students from the nation's elite class. In the 1920s, the German-funded Amani High School opened in Kabul, and about a decade later two French lycées (secondary schools) began, the AEFE and the Lycée Esteqlal. During the same period the Kabul University opened its doors for classes. Education was improving in the country by the late 1950s, during the rule of King Zahir Shah. However, after the Saur Revolution in 1978 until recent years, the education system of Afghanistan fell apart due to the wars. It was revived in the early months of 2002 after the US removed the Taliban and the Karzai administration came to power.

As of 2009 more than five million male and female students were enrolled in schools throughout the country. However, there are still significant obstacles to education in Afghanistan, stemming from lack of funding, unsafe school buildings and cultural norms. Furthermore, there is a great lack of qualified teachers, especially in rural areas. A lack of women teachers is another issue that concerns some Afghan parents, especially in more conservative areas. Some parents will not allow their daughters to be taught by men.[179]

UNICEF estimates that more than 80 percent of females and around 50 percent of males lack access to education centers. According to the United Nations, 700 schools have been closed in the country because of poor security.[180] Literacy of the entire population is estimated at 34%. Female literacy is 10%.[180] The Afghan ministry of education, assisted by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), is in the process of expanding education in the country by building more new schools and providing modern technologies.

Following the start of the U.S. mission in late 2001, Kabul University was reopened to both male and female students. In 2006, the American University of Afghanistan also opened its doors, with the aim of providing a world-class, English-language, co-educational learning environment in Afghanistan. The university accepts students from Afghanistan and the neighboring countries. Many other universities were inaugurated across the country in recent years, such as Kandahar University in the south, Herat University in the northwest, Balkh University in the north, Nangarhar University and Khost University in the eastern zones, and others. The National Military Academy of Afghanistan has been set up to train and educate Afghan soldiers.

Law enforcement

Afghanistan currently has more than 90,000 national police officers, with plans to recruit more so that the total number can reach 160,000. The Afghan National Police and Afghan Border Police are under the Afghan Interior Ministry, which is today headed by Bismillah Khan Mohammadi. Although they are being trained by NATO countries and through the Afghanistan Police Program, there are still many problems with the force. Large percentage of the police officers are illiterate and are widely accused of demanding bribes.[181]

Approximately 17 percent of them test positive for illegal drugs. In some areas of the country, crimes have gone uninvestigated because of insufficient police or lack of equipment. In 2009, President Karzai created two anti-corruption units within the nation's Interior Ministry.[182] Former Interior Minister Hanif Atmar told reporters that security officials from the U.S. (FBI), Britain (Scotland Yard) and the European Union (ELOPE) will train prosecutors in the unit.[183]

Helmand, Kandahar, and Oruzgan are the most dangerous provinces in Afghanistan due to its distance from Kabul as well as the drug trade that flourishes there. The Afghan Border Police are responsible for protecing the nation's borders, especially the Durand Line border, which is often used by criminals and terrorists. Every year many Afghan police officers are killed in the line of duty.

Culture

Afghans display pride in their religion, country, ancestry, and above all, their independence. Like other highlanders, Afghans are regarded with mingled apprehension and condescension, for their high regard for personal honor, for their clan loyalty and for their readiness to carry and use arms to settle disputes.[184] As clan warfare and internecine feuding has been one of their chief occupations since time immemorial, this individualistic trait has made it difficult for foreign invaders to hold the region.

Afghanistan has a complex history that has survived either in its current cultures or in the form of various languages and monuments. However, many of the country's historic monuments have been damaged in recent wars.[185] The two famous statues of Buddha in Bamyan Province were destroyed by the Taliban, who regarded them as idolatrous. Other famous sites include the cities of Kandahar, Herat, Ghazni and Balkh. The Minaret of Jam, in the Hari River valley, is a UNESCO World Heritage site. A cloak reputedly worn by Muhammad is stored inside the famous Mosque of the Cloak of the Prophet Mohammed in Kandahar City.

Buzkashi is a national sport in Afghanistan. It is similar to polo and played by horsemen in two teams, each trying to grab and hold a goat carcass. Afghan hounds (a type of running dog) also originated in Afghanistan.

Although literacy levels are very low, classic Persian poetry plays a very important role in the Afghan culture. Poetry has always been one of the major educational pillars in Iran and Afghanistan, to the level that it has integrated itself into culture. Persian culture has, and continues to, exert a great influence over Afghan culture. Private poetry competition events known as "musha’era" are quite common even among ordinary people. Almost every homeowner owns one or more poetry collections of some sort, even if they are not read often.

The eastern dialects of the Persian language are popularly known as "Dari". The name itself derives from "Pārsī-e Darbārī", meaning Persian of the royal courts. The ancient term Darī – one of the original names of the Persian language – was revived in the Afghan constitution of 1964, and was intended "to signify that Afghans consider their country the cradle of the language. Hence, the name Fārsī, the language of Fārs, is strictly avoided."[186]

Many of the famous Persian poets of the tenth to fifteenth centuries stem from what is now known as Afghanistan (then known as Khorasan), such as Jalal al-Din Muhammad Balkhi (also known as Rumi or Mawlānā), Rābi'a Balkhi (the first poetess in the history of Persian literature), Khwaja Abdullah Ansari (from Herat), Nasir Khusraw (born near Balkh, died in Badakhshan), Jāmī of Herāt, Alī Sher Navā'ī (the famous vizier of the Timurids), Sanā'ī Ghaznawi, Daqiqi Balkhi, Farrukhi Sistani, Unsuri Balkhi, Anvari, and many others. Moreover, some of the contemporary Persian language poets and writers, who are relatively well-known in Persian-speaking world, include Khalilullah Khalili,[187] Sufi Ashqari,[188] Sarwar Joya, Qahar Asey, Parwin Pazwak and others.

In addition to poets and authors, numerous Persian scientists and philosophers were born or worked in the region of present-day Afghanistan. Most notable was Avicenna (Abu Alī Hussein ibn Sīnā) whose paternal family hailed from Balkh. Ibn Sīnā, who travelled to Isfahan later in life to establish a medical school there, is known by some scholars as "the father of modern medicine". George Sarton called ibn Sīnā "the most famous scientist of Islam and one of the most famous of all races, places, and times." His most famous works are The Book of Healing and The Canon of Medicine, also known as the Qanun. Ibn Sīnā's story even found way to the contemporary English literature through Noah Gordon's The Physician, now published in many languages.

Al-Farabi was another well-known philosopher and scientist of the 9th and 10th centuries, who, according to Ibn al-Nadim, was from the Faryab Province in Afghanistan. Other notable scientists and philosophers are Abu Rayhan Biruni (a notable astronomer, anthropologist, geographer, and mathematician of the Ghaznavid period who lived and died in Ghazni), Abu Zayd Balkhi (a polymath and a student of al-Kindi), Abu Ma'shar Balkhi (known as Albumasar or Albuxar in the west), and Abu Sa'id Sijzi (from Sistan).

Before the Taliban gained power, the city of Kabul was home to many musicians who were masters of both traditional and modern Afghan music, especially during the Nauroz-celebration. Kabul in the middle part of the twentieth century has been likened to Vienna during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

There are an estimated 60 major Pashtun tribes.[189] The tribal system, which orders the life of most people outside metropolitan areas, is potent in political terms. Men feel a fierce loyalty to their own tribe, such that, if called upon, they would assemble in arms under the tribal chiefs and local clan leaders. In theory, under Islamic law, every believer has an obligation to bear arms at the ruler's call.

Heathcote considers the tribal system to be the best way of organizing large groups of people in a country that is geographically difficult, and in a society that, from a materialistic point of view, has an uncomplicated lifestyle.[184]

The population of nomads in Afghanistan is estimated at about 2-3 million.[190] Nomads contribute importantly to the national economy in terms of meat, skins and wool.

Media

The media was tightly controlled under the Taliban, as television was shut down in 1996 and print media were forbidden to publish commentary, photos or readers letters.[191] The only radio station broadcast religious programmes and propaganda, and aired no music.[191] After the new government of 2001, press restrictions were gradually relaxed and private media diversified. Freedom of expression and the press is promoted in the 2004 constitution and censorship is banned, though defaming individuals or producing material contrary to the principles of Islam is prohibited. In 2008, Reporters Without Borders listed the media environment as 156 out of 173, with 1st being most free.[192] 400 publications are now registered, at least 15 local Afghan television channels and 60 radio stations.[193] Foreign radio stations, such as the BBC World Service, also broadcast into the country.

Notes

| a.^ | Other terms that can be used as demonyms are Afghani[194] and Afghanistani.[195] |

See also

- List of Afghanistan-related topics

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Afghanistan". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2007-12-13. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/af.html. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2009) (PDF). World Population Prospects, Table A.1. 2008 revision. United Nations. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2008/wpp2008_text_tables.pdf. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Afghanistan". International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2007&ey=2010&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=512&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a=&pr.x=40&pr.y=11. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ "Afghanistan". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/7798/Afghanistan. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Census of India - Map of Jammu & Kashmir". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. http://censusindia.gov.in/maps/State_Maps/StateMaps_links/j_k.html. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ http://premadasi.files.wordpress.com/2009/11/india-map.jpg

- ↑ The Afghan wars, 1839–1919, by T. A. Heathcote (1980), page 7.

- ↑ Craig Baxter (1997). "Chapter 1. Historical Setting". Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID%2Baf0001). Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ "Kingdoms of South Asia - Afghanistan in Far East Kingdoms: Persia and the East". The History Files. http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsMiddEast/EasternAfghans.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ D. Balland (2010). "AFGHANISTAN x. Political History". Encyclopædia Iranica (Encyclopædia Iranica Online ed.). Columbia University.

- ↑ M. Longworth Dames, G. Morgenstierne, and R. Ghirshman (1999). "AFGHĀNISTĀN". Encyclopaedia of Islam (CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0 ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ↑ Ahmad Shah Durrani, Britannica Concise.

- ↑ The Decline of the Pashtuns in Afghanistan, Anwar-ul-Haq Ahady, Asian Survey, Vol. 35, No. 7. (Jul., 1995), pp. 621–634.

- ↑ Interview with J Carter security adviser

- ↑ "State of the Insurgency Trends, Intentions and Objectives". ISAF. DefenseStudies.org. December 22, 2009. http://www.defensestudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/isaf-state-of-the-insurgency-231000-dec.pdf.

- ↑ Cowan, William and Jaromira Rakušan. Source Book for Linguistics. 3rd ed. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1998.

- ↑ Morgenstierne, G. (1999). "AFGHĀN". Encyclopaedia of Islam (CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0 ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ↑ Nancy Hatch Dupree – The Story of Kabul (Mongols).

- ↑ Willem Vogelsang, The Afghans, Edition: illustrated Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2002, Page 18, ISBN 0631198415, 9780631198413: "... Looking for the origin of Pashtuns and the Afghans is something like exploring the source of the Amazon. Is there one specific beginning? And are the Pashtuns originally identical with the Afghans? Although the Pashtuns nowadays constitute a clear ethnic group with their own language and culture, there is no evidence whatsoever that all modern Pashtuns share the same ethnic origin. In fact it is highly unlikely."

- ↑ "Afghan" (with ref. to "Afghanistan: iv. Ethnography") by Ch. M. Kieffer, Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition 2006.

- ↑ extract from "Passion of the Afghan" by Khushal Khan Khattak; translated by C. Biddulph in "Afghan Poetry Of The 17th Century: Selections from the Poems of Khushal Khan Khattak", London, 1890.

- ↑ "Transactions of the year 908" by Zāhir ud-Dīn Mohammad Bābur in Bāburnāma, translated by John Leyden, Oxford University Press: 1921.

- ↑ Elphinstone, M., "Account of the Kingdom of Cabul and its Dependencies in Persia and India", London 1815; published by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown.

- ↑ E. Bowen, "A New & Accurate Map of Persia" in A Complete System Of Geography, Printed for W. Innys, R. Ware [etc.], London 1747.

- ↑ E. Huntington, "The Anglo-Russian Agreement as to Tibet, Afghanistan, and Persia", Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, Vol. 39, No. 11 (1907).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 MECW Volume 18, p. 40; The New American Cyclopaedia – Vol. I, 1858.

- ↑ M. Ali, "Afghanistan: The War of Independence, 1919", Kabul [s.n.], 1960.

- ↑ Afghanistan's Constitution of 1923 under King Amanullah Khan (English translation).

- ↑ University of California, Center for South Asia Outreach, University of Pennsylvania, World Bank; U.S. maps; University of Washington Syracuse University.

- ↑ "The 2007 Middle East & Central Asia Politics, Economics, and Society Conference September 6–8, 2007" (pdf). University of Utah, Salt Lake City. http://web.utah.edu/meca/2007Conf/2007%20MECA-%20Final%20Program.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ "Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East & Central Asia, May 2006" (pdf). International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/reo/2006/eng/01/mreo0506.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ "CRS: Middle East Elections 2009: Lebanon, Iran, Afghanistan, and Iraq".

- ↑ "History of Environmental Change in the Sistan Basin 1976–2005" (PDF). http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/sistan.pdf. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Afghanistan's woeful water management delights neighbors

- ↑ Afghanistan, CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Gold and copper discovered in Afghanistan.

- ↑ Uranium Mining Issues: 2005 Review.

- ↑ 16 detained for smuggling chromites, Pajhwok Afghan News.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 U.S. Identifies Vast Riches of Minerals in Afghanistan

- ↑ Afghanistan minister says country's mineral wealth could exceed $3 trillion

- ↑ Afghan mineral wealth may be greater: $3 trillion

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 John Ford Shroder, University of Nebraska. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Nancy H. Dupree (1973): An Historical Guide To Afghanistan, Chapter 3 Sites in Perspective.

- ↑ Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan, Pre-Islamic Period, by Craig Baxter (1997).

- ↑ Bryant, Edwin F. (2001) The quest for the origins of Vedic culture: the Indo-Aryan migration debate Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, ISBN 0-19-513777-9.

- ↑ Afghanistan: ancient Ariana (1950), Information Bureau, London, p3.

- ↑ M. Witzel, "The Vīdẽvdaδ list obviously was composed or redacted by someone who regarded Afghanistan and the lands surrounding it as the home of all Aryans (airiia), that is of all (eastern) Iranians, with Airiianem Vaẽjah as their center." page 48, "The Home Of The Aryans", Festschrift J. Narten = Münchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft, Beihefte NF 19, Dettelbach: J.H. Röll 2000, 283-338. Also published online, at Harvard University (LINK)

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan, Achaemenid Rule, ca. 550-331 B.C.

- ↑ The history of Afghanistan, Ghandara.com website.

- ↑ Afghanistan: Achaemenid dynasty rule, Ancient Classical History, about.com.

- ↑ Nancy H. Dupree, An Historical Guide to Kabul

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 History of Afghanistan, by Abdul Sabahuddin. First edition, 2008, p 20. ISBN 81-8220-246-9

- ↑ Country Profile: Afghanistan, August 2008, Library of Congress Country Studies

- ↑ Dani, A. H. and B. A. Litvinsky. "The Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom". In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B. A., ed., 1996. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 103–118. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.

- ↑ Zeimal, E. V. "The Kidarite Kingdom in Central Asia". In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B. A., ed., 1996, Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 119–133. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.

- ↑ Litvinsky, B. A. "The Hephthalite Empire". In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B. A., ed., 1996, Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 135–162. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.

- ↑ Dehkhoda Dictionary, by Ali Akbar Dehkhoda, p. 8457.

- ↑ Khorasan (1947), by Mir Ghulam Ghobar

- ↑ Iranica, "ASAD B. SĀMĀNḴODĀ, ancestor of the Samanid dynasty"